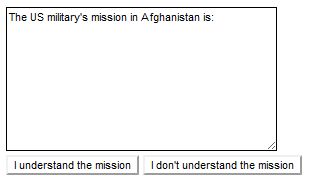

Pop quiz: Can you summarize specific, concrete objectives for our military in Afghanistan? If so, please write them in the space provided below:

>If you

Finally, convince your fellow citizens that spending billions each month to meet these objectives is more important than investing in jobs, growth, education, or a crumbling national infrastructure.

A Tough Assignment

thought this quiz was hard, you have a pretty good idea why the President gave himself a tough assignment for last night's speech. A nation in the midst of a prolonged recession is increasingly impatient with a war that's approaching its ten year anniversary. A poll conducted over the last week showed that nearly one-third of all Americans want an immediate withdrawal from Afghanistan, and a majority want to see us out in the next couple of years.

The President withdrew approximately 100,000 troops from Iraq, to widespread public approval and with no apparent political blowback. That was the right move. But troop levels in Afghanistan have risen dramatically under his command. With Al Qaeda on the move, Bin Laden dead, and no clear goals on the ground, he gave himself an impossible task: to explain why it's a good idea to withdraw some troops, while also trying to prop up support for leaving most of the others in place for the foreseeable future.

We were told that 10,000 troops will be out of Afghanistan by the end of the year, with the rest of President Obama's troop "surge" (another 23,000) withdrawn by September of 2012. But that still leaves 68,000 troops where there were less than half as many at the beginning of 2008. Some people will agree with Tom Hayden that this is a victory for the peace movement. Others will see it as a manipulative attempt at prolonging an unpopular war. Either belief leads to the same conclusion: The best course is keep up the political pressure for a prompt withdrawal.

Guns and Butter

The human price of our Afghan venture, military and civilian deaths and injuries, has been sadly invisible to the American people most of the time. But they're acutely aware of their own financial situation, and that's fueling a growing sense of unease about this long and costly war.

The country's in a state of economic gloom. Almost everyone is close to a household that's been touched by unemployment or foreclosure. Those fortunate enough to have jobs are fearful, too. Nine out of ten expect their income to fall behind inflation next year, according to a recent poll, and 70% expect to cut back their purchases to cover only necessities.

Pessimism is bad for the economy. It also creates a hostile political climate for a combined war effort that costs more than ten billion dollars every month. "Why spend the money over there," goes the refrain, "when we need it over here?" While that question may ignore the political reality of a Republican Congress ready to veto any and all common-sense domestic spending measures, it helps to illustrate the political hypocrisy behind Washington's new "austerity economics" craze.

It also explains why the National Conference of US Mayors, which includes mayors from across the political spectrum, just adopted a resolution asking the President and Congress "to end the wars as soon as strategically possible and bring these war dollars home to meet vital human needs, promote job creation, rebuild our infrastructure, aid municipal and state governments, and develop a new economy based upon renewable,sustainable energy and reduce the federal debt."

These mayors deal with brutal economic realities every day. As their report says, "75 (metropolitan areas) will have double-digit unemployment rates, and 193 (53%) will have rates higher than 8%. At the end of 2012, 311 (metropolitan areas) will have unemployment rates above 6%; 173 will have rates above 8%; and 69 above 10%."

"Mission Creep"? We should be so lucky.

Anybody who believes in Clemenceau's maxim that "war is too important to be left to the generals" has never tried telling it to a general. They disagree, and pretty vehemently. So do cable TV newspeople, one of whom asked me last night: "Why shouldn't the generals have the final say about the timetable for withdrawal?"

The first answer to that question is, because they chose to practice their profession in a nation where civilians supposedly control the military. But the second, more specific answer is this: Without a well-defined mission, the generals don't have the benchmarks to set a reasonable schedule for withdrawal.

In World War II and other "normal" wars, it was easy to know when victory had been achieved. It was when Rome and Berlin fell, or when Hirohito surrendered. Afghanistan isn't like that. Al Qaeda's on the move. Tribal loyalties keep shifting. Corruption touches everything. Even "mission creep," that curse of wars, seems like a well-structure agenda compared to Afghanistan.

And if there's no clear mission, why are we there at all?

A Constituency of Generals

Even those of us who stand by Clemenceau's words know that generals are a powerful constituency for any President. Obama seems to be meeting with firm resistance from the Joint Chiefs (if recent reports are to be believed).

Military leaders have the power to cause considerable political damage to any President, especially a Democrat. Admiral Mike Mullen, head of the Joint Chiefs, said today expressed tepid support for the President's withdrawal plans while saying they"more aggressive and incur more risk" than he advised. (It's ironic when a military leader describes a troop reduction as "more aggressive," isn't it?) Mullen added: "More force for more time is, without doubt, the safer course."

Admiral Mullen's statement isn't very clear or coherent. Safety for whom - our troops? They'd be safest at home. For the Afghans? How are we protecting them, exactly? But although it was unclear in many ways, his warning to the President seemed clear enought: Don't push this withdrawal business too far.

Ambiguities and Endgames

But whatever the risk of incurring the military's wrath, the President may be running an even greater risk by trying to ride a wave of ambiguity. The Democrats' vague statements about the value of government in general, and entitlements in particular, allowed hard-right Republicans to run to the President's left in 2010 on Medicare. Presidential ambivalence about Afghanistan could let them do the same on the war in 2012. Jon Huntsman tried it this week when he called for "an aggressive drawdown" and said "it's an issue of priorities."

The President's observation that by "the Afghan people will be responsible for their own security" raises more questions than answers. If they're responsible for their own security in 2014, why aren't all our troops coming home then? And Americans won't take orders from Afghan commanders, so what does this statement mean?

Mr. Obama gave some red-meat language for liberals, as he often does. "America," he said, "it is time to focus on nation building here at home." But his list of Afghan successes works better as an argument for a quick withdrawal than it does for a slow one. And his statement that "the light of a secure peace can be seen in the distance" may remind older Americans of the often repeated Vietnam-era reassurance that there's "light at the end of the tunnel."

An economically struggling United States is running out of patience with a struggle that's costly in blood and treasure. The public is being sold on the need for this war at the same time that it's being sold on the idea that we can end it. No wonder they're confused, especially since this war's stated purpose was to "get" the people who attacked us on 9/11.

Okay, people seem to be saying. They've been "got." Shouldn't we be going now?

The last President declared "Mission Accomplished" too soon. It would be tragic if this one declared it too late.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.